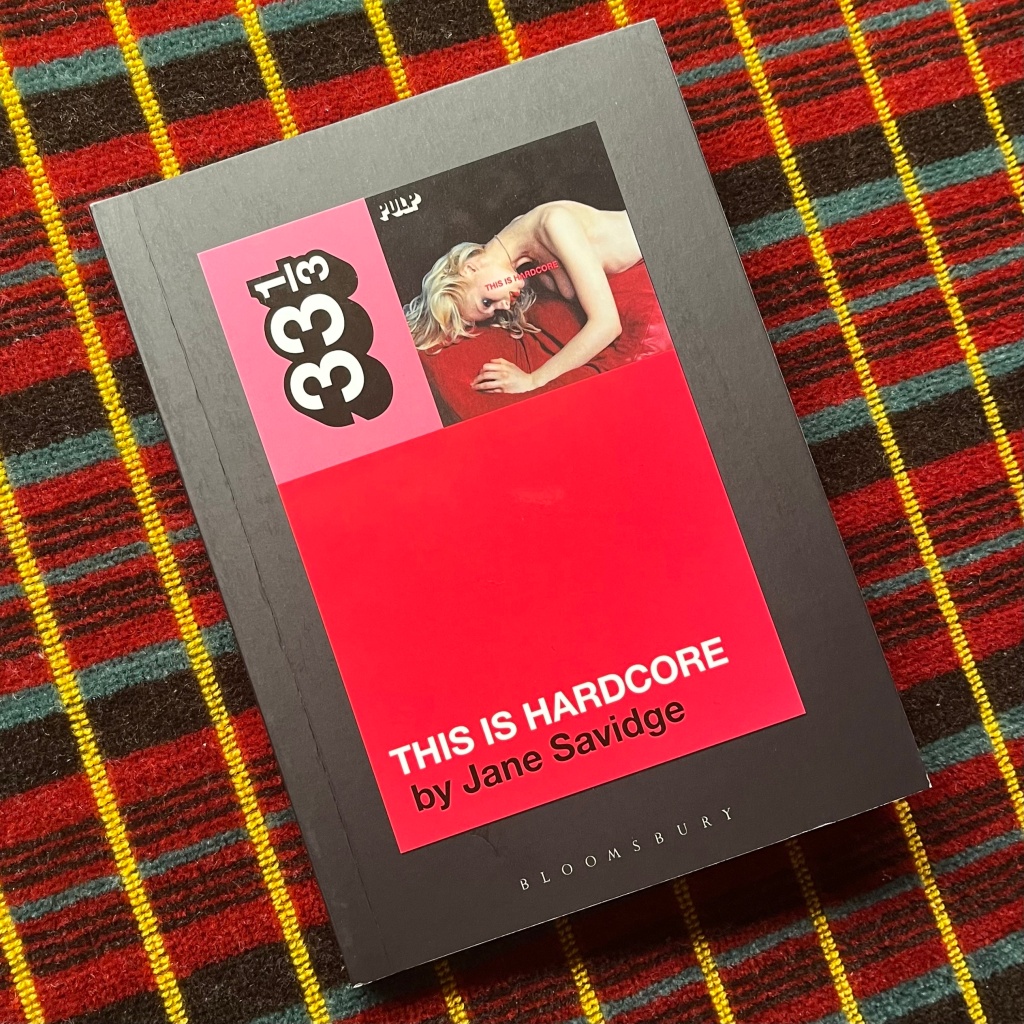

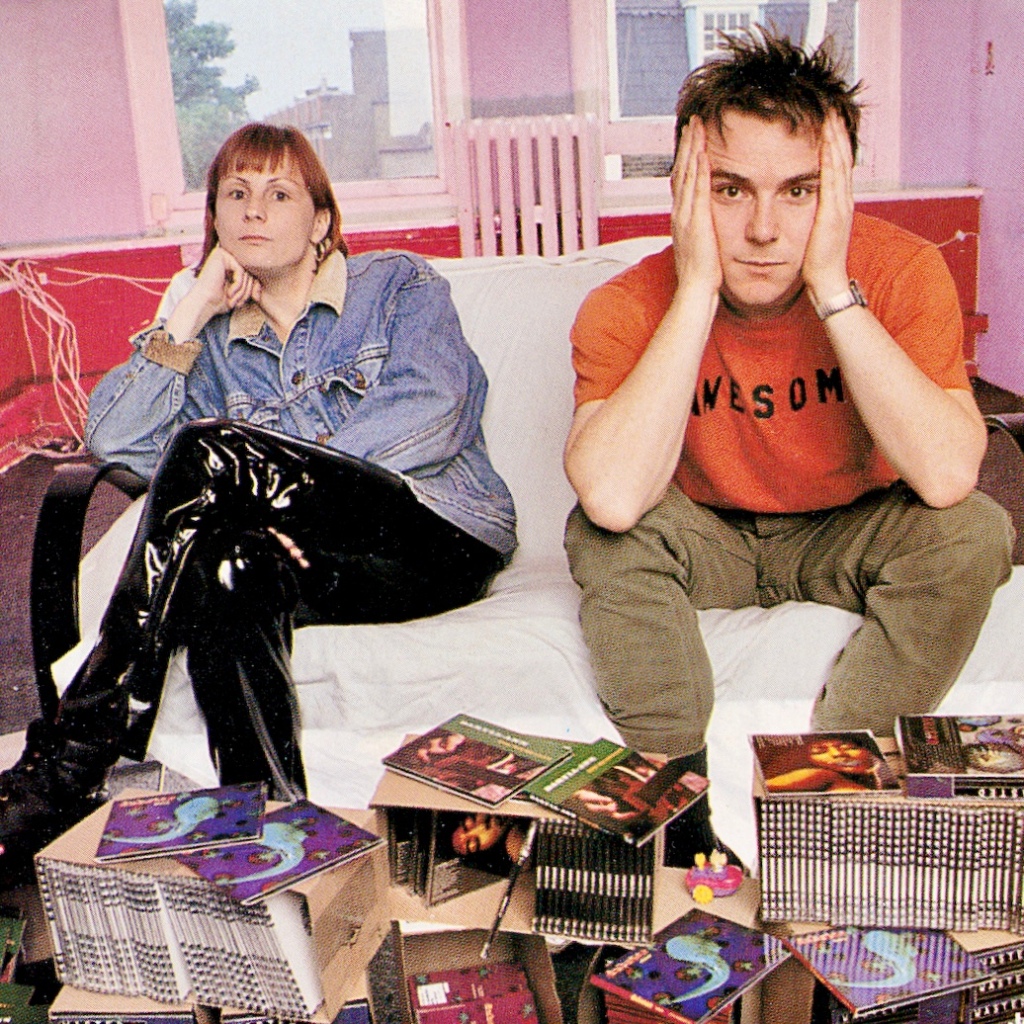

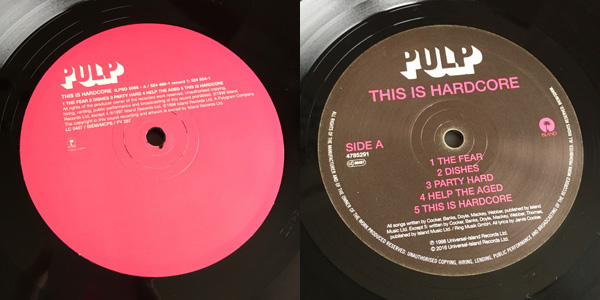

This Is Hardcore is the first Pulp album to feature in the 33⅓ series of music books about influential albums. Jane Savidge is ideally placed to tell the story of This Is Hardcore. Alongside John Best she co-founded Savage & Best, with Pulp being one of a large roster of bands they helped to get press coverage for. To describe Savage & Best as successful is an understatement. They were a phenomenon. Based in the heart of Camden Town, they were propelled by a group of young people who – most importantly – were passionate about good music, and – less importantly – brilliant at generating publicity for the bands they represented.

Like last year’s Nick Banks interview, this is another long read. The interview is split into four parts that cover a different aspect of Jane’s work and her relationship with Pulp.

Part 1: Jane and Savage & Best

Acrylic Afternoons (AA): For those who aren’t familiar with your first book, ‘Lunch With The Wild Frontiers’, can you explain the role of a music PR in the 1990s?

Jane: The job has completely changed now, but I used to describe it as being a ‘music taste evangelist’. Basically I would find bands that I loved and tell everybody about them. In those days my friends were music journalists writing for the NME, Melody Maker, Sounds and Record Mirror. Many of those journalists went on to write for the broadsheet newspapers. In that intense period in the early 90s, some people felt that a publicist shouldn’t get too too close to their artist, whereas other people felt that you should protect the artist rather than being a friend of the journalist. So you had a delicate balancing act.

You always have to represent the artists that you look after to the best of your ability and stop them doing things that you don’t think are a good idea. I hated the tabloid newspapers and I used to say that my bands would never speak to the Daily Mail, and no-one ever questioned that. Obviously I was being a bit ridiculous but people would say to me, “Oh okay… fair enough” and that would be fine. But then it got to a point where the bands I looked after – Suede, Pulp, Elastica, The Verve, Spiritualized, Jesus And The Mary Chain, The Charlatans – became so big that all the tabloids wanted to write about them. That’s when I felt uncomfortable because I didn’t think those bands belonged in the tabloids. But they were selling so many records those papers had to write about them.

When Pulp became famous The Mirror rang me every day to try to get a story. I refused to call them back. The guy who ran the gossip pages said, “Savage & Best must be the worst press company in Britain because they’re not returning my calls”. I didn’t want to speak to them and felt that my bands were perfectly okay without them. He did this every day until a couple of people in the office said that it might be damaging the reputation of Savage & Best. So I rang him just to say hello and the next day he said, “Oh look Savage & Best rang back”. It was all part of their bullying nature.

AA: Presumably they were going to write stuff about your bands anyway, with or without your cooperation?

Jane: That’s the fine line between saying ‘No Comment’ or getting involved in the story, because you can pour fuel on it. There was lots of gossip going around about drugs and I didn’t want to comment on that because it’s got nothing to do with the music.

AA: Your first book makes the world of a music PR seem impossibly glamourous from the perspective of an outsider. How much time was spent having fun and how much was hard work?

Jane: It was impossibly glamourous! Everybody in the office was the same age. We were all in our 20s and nobody really had a boyfriend or a girlfriend, so we worked late. On Wednesdays we went to the recording of Top Of The Pops, which was broadcast on Thursdays. On Fridays one of us went to the recording of TFI Friday because we always had one of our bands on. I once had five bands on Top Of The Pops on the same night. We often went to pubs around Camden for the gigs and then went back to the office afterwards. We’d stay there until midnight listening to music and doing things we shouldn’t have been doing.

We were also the same age as the bands we looked after. Jarvis and Steve came into the office a fair amount because they liked Camden. It helped that we didn’t have a financial stake in the band. We were genuinely in love with the music and did it for monthly retainers just to keep the office going. People could tell that we genuinely loved the bands, so the bands liked hanging around with us.

AA: Was that the office where Polly [Birkbeck, Senior Press Officer at Savage & Best] would take the Polaroid photos of the artists and display them on the wall?

Jane: That’s the one. In the downstairs office was an architect’s practice. All the people who came to see us first had to sign their name in the architect’s reception book. You know… ’Jason from Spiritualized’. If we still had that book it would be worth thousands. More pop-stars than architects.

AA: Within the Savage & Best team, did everyone share the same opinion about what made Pulp great?

Jane: I’d say that me and Polly were quite similar. I was obsessed with image and style. Lyrics and androgyny were important too, so I completely understood the Manic Street Preachers. I once worked with a US band called Suicidal Tendencies. When I met the singer he drank Diet Coke and afterwards I gave him a lift in my car and he put his seatbelt on. I thought, ‘Hang on, you’re called Suicidal Tendencies and you’re drinking Diet Coke and wearing seat belts?’ I asked him why he wanted to be in a band and he said, “So I can have a house as big as my gran”. If that was true and you were British, no-one would buy your records ever again! What a completely different mentality. In the UK you’d probably say, “I wanna become famous so I can kill my gran”.

But in terms of how I differed to the others, I was a bit more chaotic. I wasn’t remotely interested in my career. I would come in to work on a Monday, go out to lunch and then return to the office on a Thursday. People would ask, “Where have you been?” I’d say, randomly, “Oh I went out with Damien Hirst… and he gave me 15 grand”. That would keep them quiet for a bit. Then I’d get tired so I would put my feet up on the sofa and call a few people.

AA: I guess there’s no rule-book for a job like that. You’re sort of making it up as you go along, right?

Jane: I was chaotic and I didn’t know what I was doing. But other people who did know what they were doing expected something different from me. For instance, Suede went to America and didn’t make it. They got flipped with The Cranberries because of the Irish connection which the Americans loved. All the press rang me to say it was over for Suede because it didn’t work out for them in America. I just went, “So the Americans didn’t get it. What great news, because we all know they’ve got shit taste!” I wasn’t saying I dislike Americans and their music, but you’ve got to put on a brave face and own the situation. By some point I became a proper publicist and had a proper career. And still people called me and expected to get a proper reply. But I never wanted to do that.

AA: Over time you’d have seen your bands get more attention, more success and more demands placed upon them. Did you have to recalibrate how you worked with the bands and your relationship with them?

Jane: We were learning on the hoof and everything was going mad at that point. Everyday the phone was ringing off the hook. I couldn’t take all the phone calls, none of us could. When I did interviews for my first book some of the interviewers asked me if I thought I worked my bands too hard, especially given the current focus on artists’ mental health. But I was not like some whip-cracking manager who coerced the bands to do something because they needed their 20%.

AA: Did they just want to interview the bands, or did they also want stories about the bands?

Jane: They wanted interviews generally. They did ask for stories about some of our newer bands. They would write about any Savage & Best band. It was ludicrous. That’s why I made up the names of new bands just to get them into the gossip columns as a joke.

Part 2: Jane & Pulp

AA: Tell us about your first encounter with Pulp.

Jane: I don’t claim to be a Pulp purist. My only connection to the band from the early days was that I went to university in Nottingham with Dolly [Peter Dalton]. He used to have ridiculously corkscrew-curly hair and kept telling me about a band he was in called Pulp. I’d heard of Pulp because I used to listen to every John Peel session, so I was semi-impressed that he used to be in the band. I don’t think he thought they were going anywhere at that point because he’d left the band. He ended up joining the Nine O’Clock Service [Sheffield-based Christianity rave cult] which Antony Genn was also a member of.

But the song that really turned me on to Pulp was My Legendary Girlfriend. There are two or three pop songs now that have that quiet-loud thing, and I was really impressed by that track. The press switched-on to it and the NME gave it Single Of The Week. At that point we were doing Lush, and Miki [Berenyi] and John [Best] were going out with each other. Miki came into the office all the time and said, “You should go to see Pulp, they’ve suddenly become fantastic”. Of course, Pulp would say that they’ve always been fantastic.

AA: So Miki had become a music taste evangelist for Pulp?

Jane: She was! Savage & Best took on Pulp when O.U. came out in 1992. So after a couple of conversations I went to see them in Brighton and at London ULU. By then Jarvis had become a raconteur. He was like one of those 1970s comedians that it was okay to like because they’re not racist. In between songs he did his little monologues. It was so funny that you almost wanted him to go on forever even though he was punctuated by these amazing songs. I don’t know whether Jarvis had that confidence in the early days. He got to that level of confidence and it probably made him think, ‘You know what, I’ll just have a chat’. That connection with an audience I don’t think I had ever seen before. He was so likeable.

I remember Polly, Melissa [Thompson], Rachel [Hendry], me and John being really excited by what was going on. But Jarvis was still shy when he came into the office. I’m not going to say he had charisma back then, but anyone who didn’t know him would be impressed by him. On stage he was so likeable and lovable that Pulp felt like a labour of love to us. It was exciting when Jarvis answered all those questions in the last round of Pop Quiz. I remember that he was so pleased that he put his hands up in the air. We all watched it in the office and we were like, ‘Fucking hell! He’s great!’ When we took Pulp on, I rang the NME and someone at their office asked me, “What have you done that for?”

AA: Let me guess: ’Damaged goods… been around for a while… not going anywhere…’ etc?

Jane: All of that, so I said to them, “Yeah, but they’ve suddenly become amazing”. An incremental thing then happened where the NME would write about them, and then the Melody Maker would do a slightly larger piece and then the NME did an even bigger piece. They were both part of the same publishing company but the titles competed against each other. They were regularly writing short pieces about Pulp, reminding people that this band from Sheffield existed. If I can be slightly cynical about it, I think Savage & Best’s success with Suede – and Suede’s success with being Suede – helped Pulp. I know that Pulp hated being lumped-in with Britpop. I collect quotes about bands that detest Britpop, I promise you they all dismiss it. I’ve been accused of lumping bands into movements to help their press profile. I admit that I did that, but I think it helped.

AA: I suppose that came from your understanding of how journalists and the music press operated?

Jane: I knew that journalists liked to think that they were the first to comment on a scene. They want to make a name for themselves and to identify that something is going on. If you tell them, ‘I’ve got a great band’, you’ll get a ‘So…?’ But if you say, ‘I’ve got four bands who sound like they come from the same place, wear the same clothes and sing about the same things’, the journalists will go, ‘Oh, that’s really interesting’.

AA: You’ve said that Andrew Harrison [Select editor] didn’t just want to put Brett and Suede on the cover and that it was your suggestion to throw in Pulp, Saint Etienne and The Auteurs?

Jane: Suede had just been put on the cover of Q, after only two singles. We’d had Suede covers with Select, NME and Melody Maker, so Select had no reason to put Suede on their cover again. They certainly didn’t want to appear to be following Q which they thought was an old man’s title! So there needed to be a reason to put them on the cover. Harrison wanted to get Pulp into a monthly magazine, but why would they write about a band that had been going for fourteen years? So positioning Pulp as part of a scene gave them a reason. We set up a photo session in a supermarket in Camden.

AA: The photo of Jarvis standing in front of the boxes of washing powder?

Jane: Yes. We put another one of our bands, The Auteurs, in that issue and Select added Denim and Saint Etienne. It was a motley collection but they all had something in common and that was Britishness. Unfortunately it became skewed with the title ‘Yanks Go Home’.

AA: And didn’t they add the Union Flag in the background without Brett knowing? To think this was not long after Morrissey at Finsbury Park.

Jane: Exactly. It was all a bit weird. I’m not ashamed to be British but I thought the ‘Yanks Go Home’ thing was a bit too much. I thought the flag was a toxic thing at the time. But the whole cover came about because we needed to get Pulp into a monthly magazine and there needed to be something to tie Pulp into. So those were the circumstances and I identify that as the first Britpop cover. As much as all those bands disassociate themselves from Britpop, the Big Five as it really is – Pulp, Suede, Blur, Elastica and Oasis – it helped them sell millions of records.

AA: What are you most proud of when you look back at your time working with Pulp?

Jane: When I saw them at Glastonbury in 1995 I felt partially involved in the possibility that they didn’t get bottled off the stage. I thought it was going to be full of pissed-up Mancs. I heard that Pulp had been rehearsing for 16-hour days or something ridiculous like that. I’m not proud as such because I had nothing to do with that.

AA: But you must’ve felt vindicated? Here was a band that you had devoted countless hours of your early career to and suddenly they were everywhere.

Jane: I did feel vindicated. But I thought Pulp were an office secret. It sounds ludicrous, but we loved them and a few people around us loved them too. But how could 100,000 people love them? What if we were wrong? What if no-one knew who they were? But it ended up being incredible. Pulp had become our biggest band at that point. Common People had charted at Number 2 as did Mis-Shapes, kept off the top spots by R*bson & Jerome and Simply Red.

AA: Oh God I’m going to have to asterisk R*bson & Jerome.

Jane: Sorry!

AA: As well as feeling vindicated, did you feel that you’d lost something? Pulp clearly weren’t an office secret anymore. They belonged to everyone.

Jane: A lot of people thought that. I thought it with R.E.M. because I saw them perform live so many times over a two year period. I even slept in my car for a couple of weeks following them around. When Losing My Religion came out, I bought the cassette. Me and my best friend played it and we just looked at each other and said, “They’re not our band anymore, are they? We’ve lost them”. That was really sad. I can’t remember if I thought the same way about Pulp. Maybe not in the same way.

AA: Were there any regrets or notable fuck-ups working with Pulp?

Jane: One of the things I most regret was taking Jarvis to the Action Man party.

AA: I sense you felt more horrified about it than he probably did. You felt responsible, right?

Jane: I did, totally responsible. Jarvis came into the office, he was going to meet Steve later and had an hour to kill. Mark Borkowski [PR guru] told me he was having this Action Man party. I said to Jarvis, “You’re going to meet Steve later, just come along to this thing with me”. I didn’t realise there were going to be so many photographers there. Borkowski said to me, “I can’t believe you bought Jarvis along!” I was thinking, ‘Well now you’ve said that, neither can I’. After that Jarvis didn’t go to any parties for three months. It probably helped him to be honest.

AA: Did you ever have to modify the requests from magazines about how they wanted Jarvis to appear in the photo shoots?

Jane: Everyone was so desperate to write a different story because you can’t do the same thing every week. The Melody Maker often took bands to Legoland.

AA: Took bands to Legoland?

Jane: Yes! Ultrasound went to Legoland. Spiritualized refused to go to Legoland, but they did a shoot in a flotation tank instead. So fair enough. But I can’t think of any things that Jarvis turned down. It got to a period, particularly for This Is Hardcore, where he did a lot of interviews. I don’t know whether it was because they’d got to a certain level of fame or whether it was to front-load all the interviews because it was a more difficult record to sell.

Part 3: Jane & Britpop

AA: There was a growing and tight-knit group of younger music types gaining influence in the early 1990s, whether as journalists, pluggers, presenters, PRs or programmers. Did that help the bands that were emerging at that time?

Jane: There was the likes of Steve Lamacq (NME, Radio 1, Deceptive Records), Stuart Maconie (Radio 1, Select, NME) and Ric Blaxill (Radio 1, Top Of The Pops). But I think something changed when Oasis joined the party. When Britpop first started – before we called it Britpop when it was just the Camden scene – people would go to Syndrome [indie club] off Oxford Street and we all socialised together. You’d get Jarvis dancing with a journalist like Siân Pattenden and you’d have Caitlin Moran sitting in the corner. Then Oasis came down, but because they became so big so quickly they arrived with their bouncers and bodyguards. It changed the mood. Oasis bought a lad mentality that became quite cartoon-like. Then, suddenly, you had roped-off areas. I never saw a roped-off area until Oasis arrived.

AA: I liked Simon Price’s observation about Britpop being a diverse and pluralistic scene long before it became a “monobrowed monoculture”.

Jane: I totally agree with that. That’s why I disagree with people who say Britpop was a sexist movement that talked women down. That’s what it became. But it wasn’t like that before. The bands that kick-started it like Suede, Pulp and Blur were never like that.

AA: That brings us to the issue of band rivalry and competition. It fuelled so much of the press attention during that time. There was something different about Pulp because they didn’t overtly slag-off their contemporaries in the way some of your other bands did to gain attention. Do you have a view on why that might be?

Jane: I think it was because Pulp were older, not by much, but it made them question what the point of that behaviour was. I think they’d seen it all already and probably felt the Britpop thing was a bit of a fad. You know… been around for 14 years and will still be around 14 years later. They’d lived through so many movements and not been associated with any of them – well done to them – so why would they fall out with another band? They had bigger fish to fry.

AA: I wonder if the other reason they avoided criticising other bands was because Pulp, well probably Steve and Jarvis chiefly, were in the middle of a social circle of artists and musicians whose lives were intertwined; collaborating together, living together and socialising together?

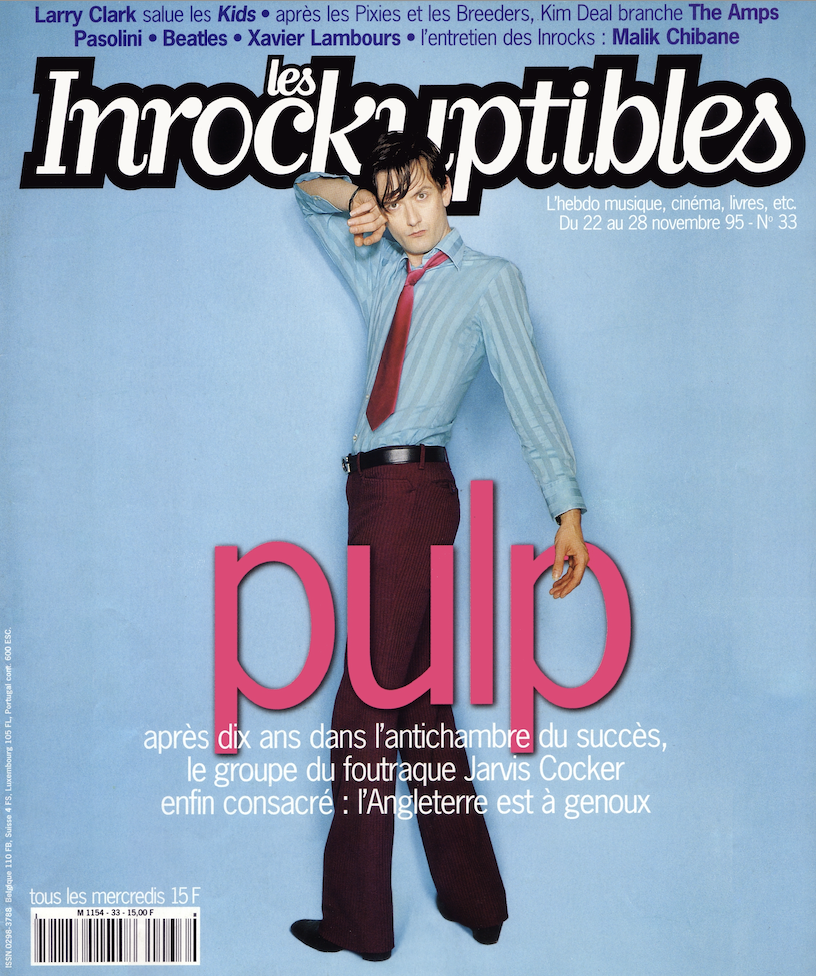

Jane: Pulp intermingled with them all, sharing flats with Elastica and Menswear. It sounds like a slur to say that Pulp weren’t offensive enough to be a rival to anybody, but there was a different vibe around them. I could tell that Pulp were an intellectual band because we got them on the cover of Les Inrockuptibles. As a student of Sartre, Camus and Baudelaire, I knew that Les Inrocks only wrote about British bands with a certain sensibility. They loved Pulp, Suede and The Auteurs because of the connection to their lyrics. There’s something very specific about Pulp’s world. Can you ever imagine Oasis having a song called Acrylic Afternoons? It was all supersonic this, and rock-n-roll that. There’s this specific world that Pulp have got, and Suede have got a similar world, that is so much more than what Blur or Oasis had.

Part 4: Jane & This Is Hardcore

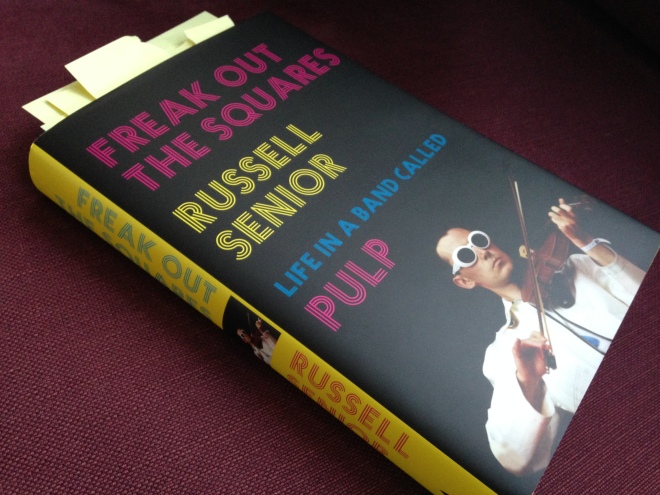

AA: From all the albums you love and are qualified to write about, what made you choose This Is Hardcore for your 33⅓ debut?

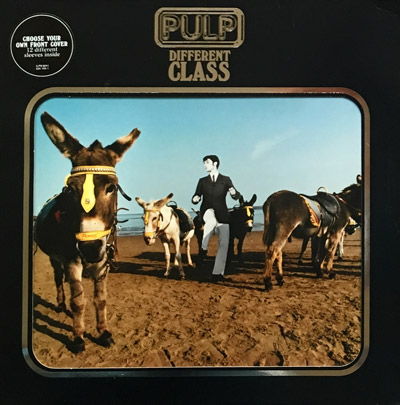

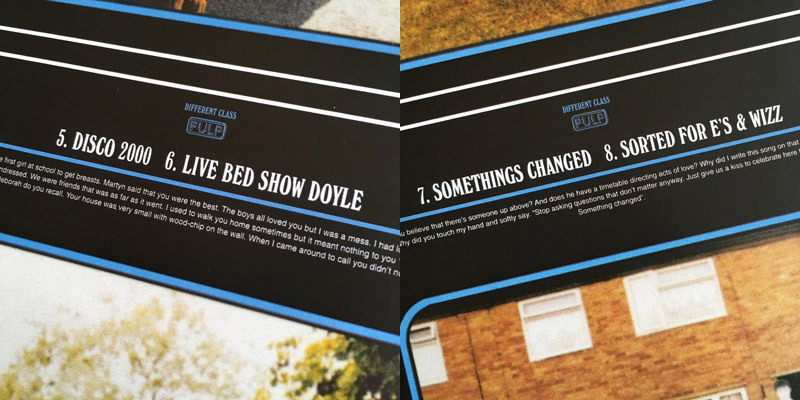

Jane: I would love to have done Murmur by R.E.M., but that had already been published, and I had already written about Suede’s Coming Up. I could’ve done Different Class but I’ve always been obsessed with This Is Hardcore because it’s a dense record with so much going on. It’s the musical equivalent of Reggie Perrin’s Grot shops. I say that because it was music that was meant to destroy something.

Consciously Jarvis wanted to kill his career because he could see it was out of control. He wanted fame for so long, and when he got it, it was the wrong kind of fame. That’s why the book starts and ends with the two fictitious stories about Jarvis calling the Total Fame Solutions helpline. I wanted to show it’s all very well wanting fame, but you’ve got to be careful what you wish for. You can get what you want, but it won’t necessarily make you feel happy. Perhaps if the MJ incident hadn’t happened Jarvis could have attained a type of fame that he was happy with. But that didn’t happen, and I think This Is Hardcore is the result of that. That’s why I chose to write about it.

AA: Fame is one of the overarching themes that straddles his lyrical output from that era.

Jane: I like that he equates fame with hardcore pornography. Not just pornography, but hardcore pornography. Your life is examined in close, minute detail. They know your address. They ring up your PR company. They track you down to your hotel room in New York. Constant attention. Because they own you in the same way that they own a naked body in pornography.

I’ve always felt that fame is like a disease. There’s that theory that if someone gets a terrible disease, their friends stop speaking to them because the friends don’t know how to deal with it. Fame is exactly the same. So you think that as much as you’ve grown up together and they’ve now become this superstar, the relationship has changed because they think I’m being their friend because they’re famous. And I could never get over that. I would go around to Brett’s house a lot and stay up late. It was always fun. But the relationship changes once you’ve helped make a band famous. If you spoke to the childhood friends of some of the people we’ve been talking about they’d probably say that they’re not the same anymore. And even if the famous person hasn’t changed, that’s not the point, because it’s their friends’ identification of the difference that makes the difference.

AA: For This Is Hardcore, there was a wider range of publications that began writing about Pulp. There was interest from international and non-music titles too. What lay behind that?

Jane: I think it was becoming more acceptable to write about bands like Pulp in those magazines. We’d already had a Sunday Times Magazine cover for Suede, and Jarvis was even more of an interesting person for those magazines. I don’t want to say I’ve got a new-found respect for Jarvis’ lyrics by writing this book, but I’ve had a reinforced respect for him as a lyricist. I’m obsessed by print magazines and newspapers, I always have been, which is why being a PR was a perfect job for me. Journalists are obsessed with lyrics. They can’t write about a D chord for very long at all, but they can examine a lyric for many pages.

AA: We’re going to have to talk about Michael Jackson now. Tell us about why you identify the 1996 Brit Awards as the ‘year zero’ moment for the events that led to This Is Hardcore.

Jane: There always has to be an ‘inciting incident’ as it were. Not just in life but also when you’re writing. There needs to be a reason behind it. When Jarvis waggled his fully-clothed bum at the King of Pop™, he didn’t know what he was unleashing. It was just a spur of the moment thing and yet it changed his life utterly into a realm of fame that he had no concept of.

It meant that if he walked down the street and a policeman came towards him, the policeman would shake his hand and ask for his autograph. It was a very strange existence. The problem with fame is that it makes people think they know you and that they own bits of you. Everything was aspirational for Jarvis before Jacko. People accused him of having writers’ block and he said, ‘No it’s just mild constipation’, which I thought was quite funny.

But what do you write about when your subject matter has changed so utterly? I think This Is Hardcore is Jarvis maturing. The type of things he was writing about: ageing, mortality, despair, drugs. It ended up being a record that couldn’t be associated with Britpop. I think he wanted it to be a record you couldn’t even associate with Pulp. It was saying goodbye to pop music but it ended up accidentally killing off Britpop.

AA: This Is Hardcore wasn’t the only difficult/awkward/dark/introspective record released at that time. You must have seen the storm clouds gathering on the horizon in 1996?

Jane: I saw it earlier with the release of Dog Man Star. It was probably the first record to try to kill off Britpop before Britpop had properly got going. I think people wanted to make less easy music.

AA: Why do you think that was?

Jane: Because it goes back to the old quote: ‘What are you rebelling against?’ ‘What have you got?’. Britpop was a reaction to grunge. What was the reaction to Britpop? Well, if Britpop was associated with easy, fun music then let’s make it as dark as possible. Everyone wanted to react against everything else going on around them.

AA: Do you remember listening to Hardcore for the first time?

Jane: You’ll know from the book the fictitious story where I to go to HMV to return the record because it doesn’t sound like Pulp. What happened in reality is that I went with John [Best] to see Geoff [Travis] and Jeannette [Lee] at Rough Trade. We sat in the Rough Trade office and Geoff said he would play us a song they had just recorded. It was This Is Hardcore and it may have been even longer than the released version. Just after it had finished, I remember saying, “Is that the single then?”

AA: Did you follow that up with, ”And will there be a radio edit?”

Jane: [Laughs] I would never, ever say that! I didn’t even mean it to be a bad thing, I just wanted to know what I was going to be working with.

AA: So What did Geoff say?

Jane: He said “Yes”. So I said, “Okay, let’s do it”, and we did the first cover with Select.

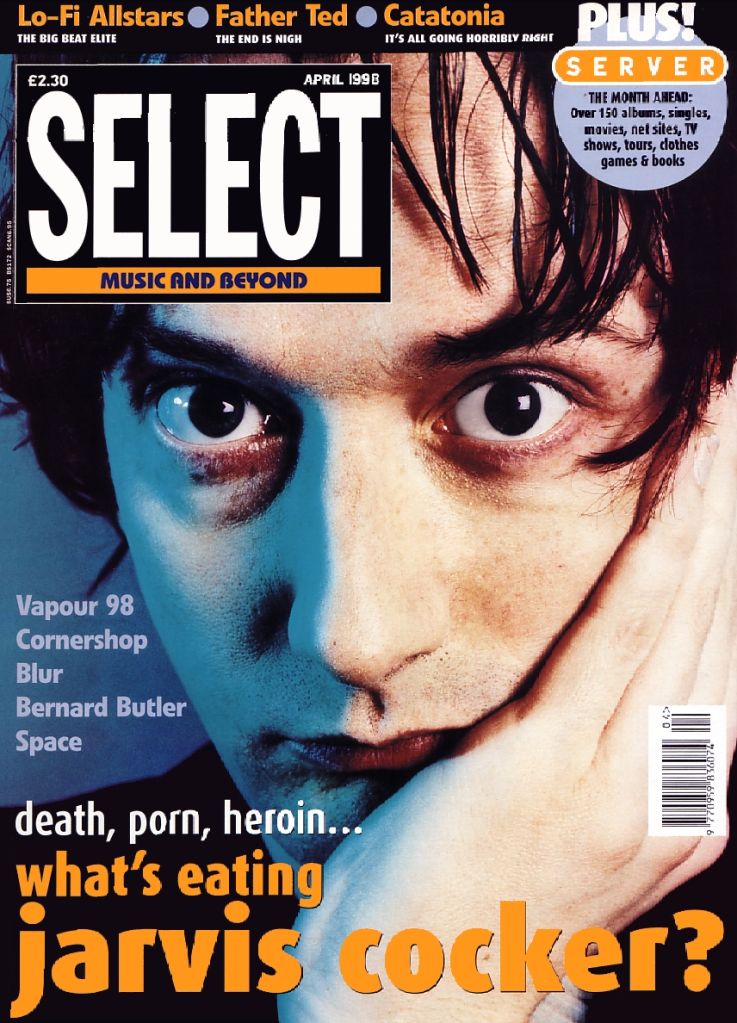

AA: Now we’re talking! “Death, Porn, Heroin… What’s eating Jarvis Cocker?”

Jane: That was the cover where everyone went, ‘Oh my God’. The band blamed me for that, I think.

AA: It was the photo shoot styling that had glamourised the heroin chic vibe, so presumably nothing to do with you?

Jane: Right. It was the most expensive photo session that Select ever commissioned. They certainly wanted it to have that kind of vibe. They wanted it to be a new kind of world that Pulp had created. And there were obviously rumours about the band doing certain drugs. So they wrote about that because I didn’t deny it, or something like that. It was a very weird time, and it set a precedent for the fucking entire campaign! And Select were completely right to do that. They had got the record right.

AA: Would the music journalists ever share the angle they intended to take on a big feature story?

Jane: Not really, although they’re more likely to do that now. But we were doing 20 interviews a day with all our bands and the journalists would never run a headline by me. They had total control. But when I saw that headline I thought, ‘God… okay, fair enough’. It was quite pointed. I re-read the article several times when I was writing the book and I can’t dispute that they got the record right.

AA: Let’s talk about The Day After The Revolution and the album’s ending. “Yeah we made it, by the skin of our teeth”. “Now all our breakdowns and nightmares look small”. Is Hardcore a redemptive album? If so, is it anything more than a pyrrhic victory and a brave face?

Jane: I think that all ties in with the millennium and being on the cusp of something new. Jarvis was getting tired of being accused of being an ironist. It was the wrong period of his life – and of the century – to be accused of irony. To answer your question I think it’s both actually. I think it was a redemptive thing. Pulp had been going for over 20 years at that point. If you’re 65 years old and have been going at something for 20 years then it feels like less than 20 years. But if you’re 34 and you’ve been going for 20 years it feels like the end of something.

AA: So you think Jarvis wanted to feel optimistic about the future?

Jane: Yes, but I think he probably felt quite old and tired by the time he’d got to that point, more so than a 65 year old would.

AA: Perhaps it was a necessity for him to feel optimistic as a way of putting behind him the trauma and the convoluted artistic process of writing about that trauma?

Jane: I occasionally punctuate the book with asides like, “This was Pulp’s 21st single”. I do that without any comment to make the reader appreciate how much water had gone under the bridge. When it comes to that song, it is the end of something. The end of irony. The end of pop music. The end of being accused of irony. Jarvis told me he liked the book. That surprised me, because I wasn’t even sure that he’d want to read about that part of his life again. So I’m quite pleased that he likes it.

AA: What are your memories of the Hardcore launch party?

Jane: It was incredibly weird and wonderful because some months previously they’d done a photo session there [the Park Lane Hilton hotel] in what must be the tackiest room in Britain. So they obviously thought it was a very appropriate place. There were five songs and I remember being exhaustively excited. It was a culmination of the madness of the record. There was also a trauma surrounding it. I probably had a drug problem at that point in my life so I think it was usual to think, ‘When are the drugs coming? Are we going to get them in time?’. I wasn’t unique in that, there was a lot of people there who felt the same way. I think many people were damaged and there was a lot of paranoia by that point. But I remember the performance being incredibly moving.

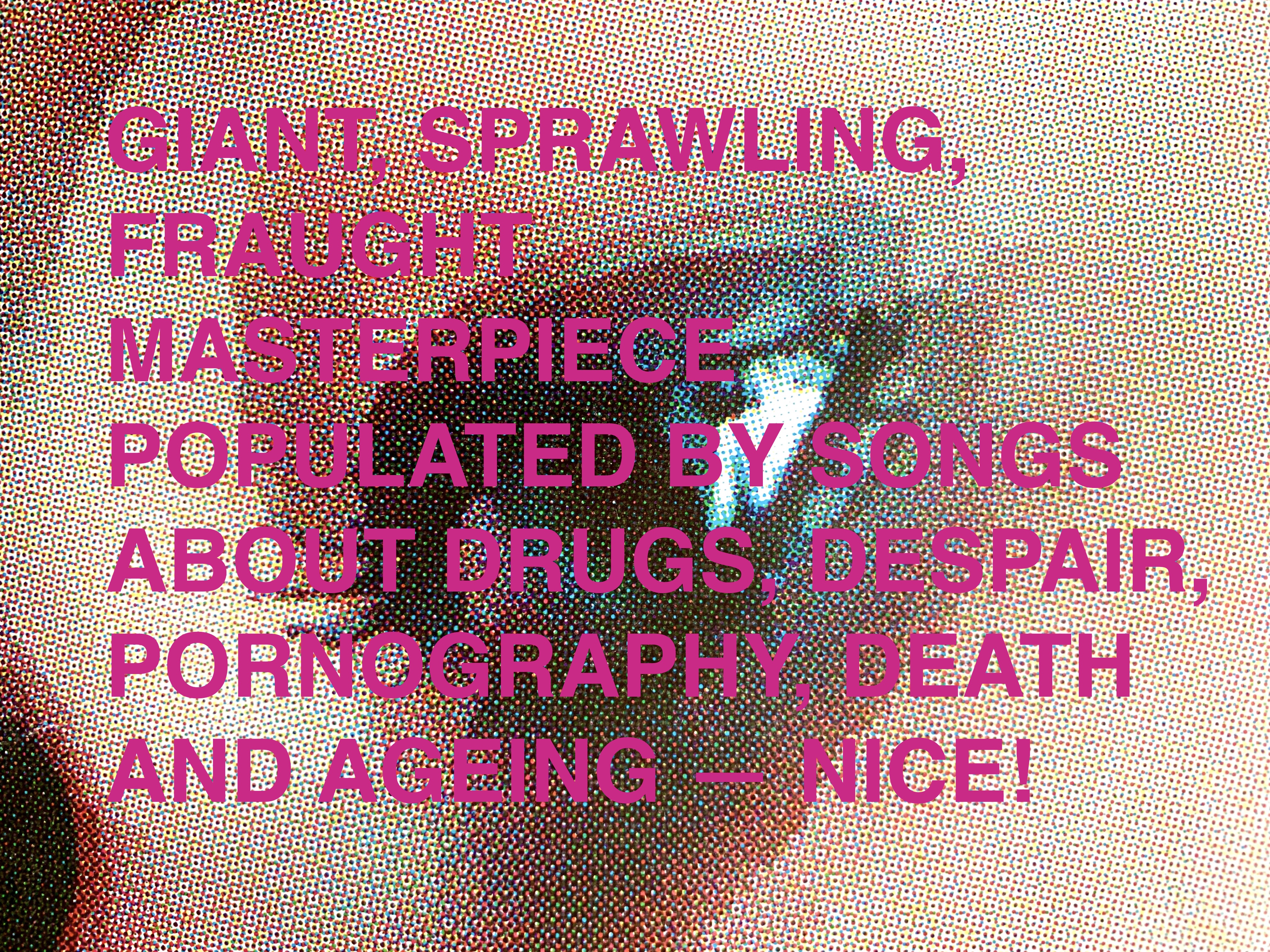

AA: Steve Lamacq once asked Jarvis to describe Different Class in 15 words (“Pop music made by people from the north of England in the mid nineteen nineties”). It’s my last question, so I’m setting you the same challenge, but instead of Different Class you have to describe This Is Hardcore in 15 words.

Jane: “Giant, sprawling, fraught masterpiece populated by songs about drugs, despair, pornography, death and ageing… hyphen… nice!”

‘This Is Hardcore’ by Jane Savidge is published by Bloomsbury on 7 March 2024.

Further reading and watching…

Read Lunch With The Wild Frontiers by Jane Savidge (2019)

View the full list of titles in the 33⅓ series

Read Fingers Crossed by Miki Berenyi (2023)

Breach Of Faith, BBC documentary on the Nine O’Clock Service (1995): YouTube

The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin, Series 2 (1977): YouTube

This Is Hardcore in pictures: The Guardian

Geoff Travis and Jeannette Lee interview (2015): The Independent

Follow Jane Savidge on Instagram

Acrylic Afternoons: Website, Twitter / X, Instagram